Students from overseas have very different effects on different bits of our higher education system. The system is now characterised by complex financial flows between tuition fees for domestic students, tuition fees for overseas students (higher), and the different types of research funding.

Anyone attempting reform of the system will have to tread carefully: it resembles one of those complicated-looking bombs in movies where the hero has to decide which colour wire to snip.

For a long time there has been a discussion about “taking students out” of net migration figures. This might seem odd to an outsider: after all, students who come to the UK to study and then leave take themselves out of the net migration figures.

Of course the real issue is that increasingly, many don’t leave, and instead move onto a work visa; or marry someone here, or claim asylum – or just disappear. That’s why over the three years to June 2024 students from outside the EU added 632,000 to net migration, and their dependants a further 225,000 – so that’s 285,000 extra people a year overall, a city-sized number each year. Around 60% of dependants were adults.

The reintroduction of the right to work after studying has (obviously) brought more students to the UK for whom work and settlement are important motives as much as the initial period of study. That plus other changes like the new post-2021 system and the care visa have also tilted the mix towards developing countries, from which staying-on rates are higher. As the ONS has noted:

More non-EU+ students and their dependants have been staying longer, and nearly 1 in 2 transitioned to a different visa type after three years from YE June 2021; an increase from 1 in 10 after three years from YE June 2019.

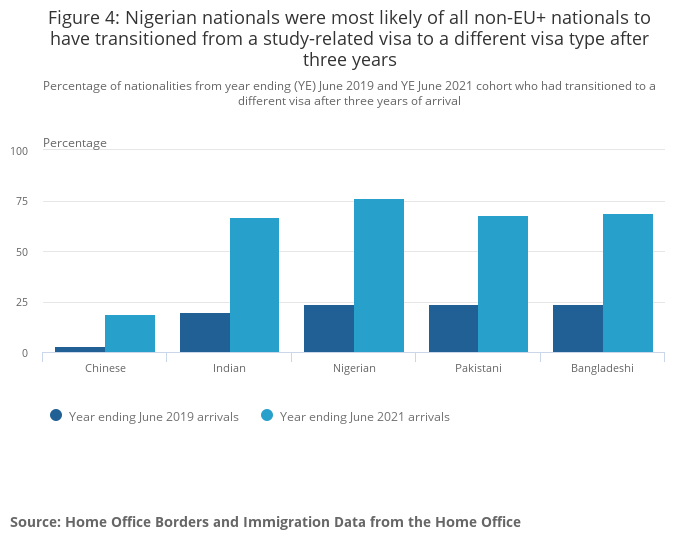

Two things are multiplying each other: the balance has shifted towards students from poorer countries who are more likely to stay, and the staying-on rate from those countries has also increased, with a large majority now shifting to other visas to allow them to stay on (plus some more on top who don’t get a visa, but don’t leave). The chart from the ONS below looks at how staying on rates have increased for the largest groups:

This is dramatic enough, but we can see that these staying-on rates are likely to increase still further – because looking at the numbers who transitioned to another visa type within one year (rather than within three years, as above), there was a substantial increase between the 2021 cohort (which is analysed in the chart above) and the 2023 cohort:

For those who arrived on a study-related visa in the year ending June 2023, 15% (63,000 people) had moved onto a family, humanitarian or other non-work visa within one year. Overall, 46% (194,000) had transitioned onto a non-study visa within one year, compared to 2% of those who arrived on such visas in 2019.

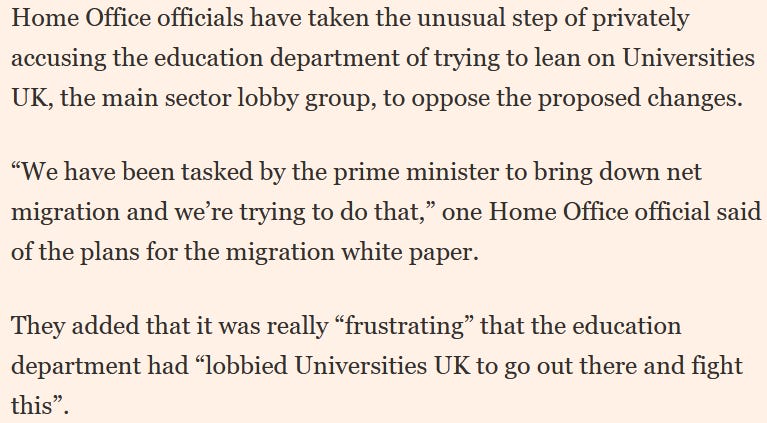

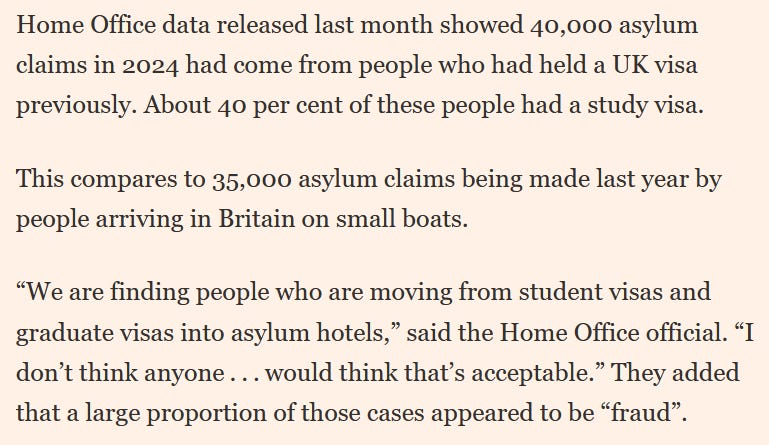

This is the reason why the Home Office and Department for Education are locked in a public tussle over the migration White Paper, which is due out next month. Some of the inter-departmental arguments have found their way into the FT:

And:

This follows hot on the heels of a series of Sunday Times exposés of ropey bottom-tier HE providers, which I wrote about recently, and wider concern about the Deliveroo visa, which I wrote about ages ago.

On the other hand, many in the sector stress the vital importance of overseas students.

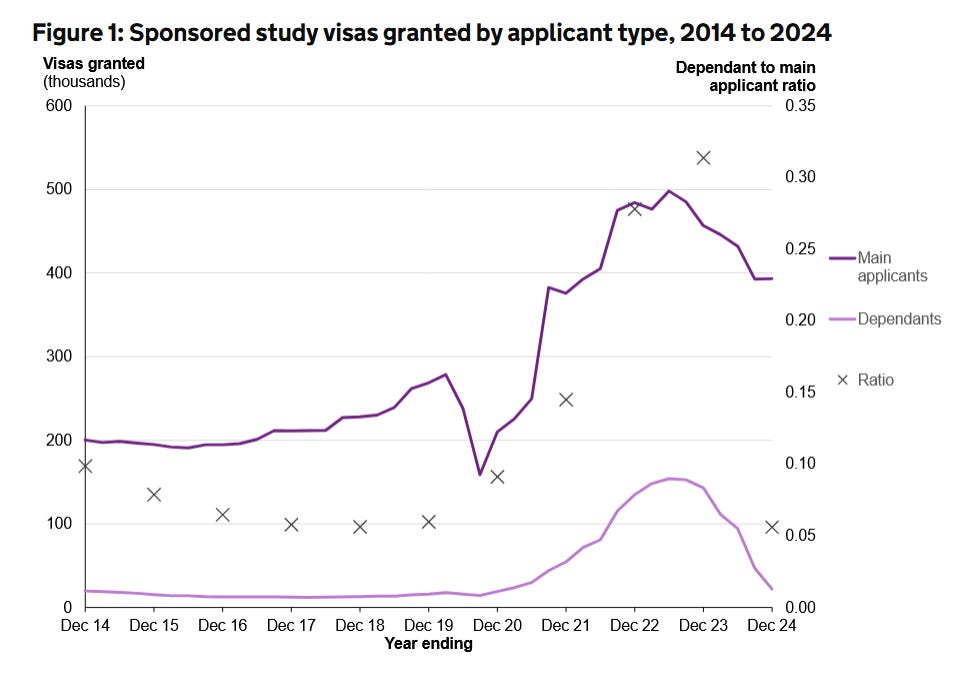

Recent years have seen some reforms of the system. In May 2023 curbs on many types of students bringing over adult and child dependants were announced, effective from January 2024. Together with changes in source countries, this reduced the numbers of dependants coming substantially, and also probably played a role in reducing the number of main applicants a bit. This has caused lots of gnashing of teeth in the sector.

It should be said though that the number of visas being issued were still twice the rate of the period 2014-2018, when the post study work visa was not available – the system is still much more liberal overall than it was a decade ago.

And while the reforms mattered, a number of the institutions that have experienced trouble had specific problems: for example, Dundee University had numerous problems, and the devaluation of Nigeria’s currency was really just the straw that broke the camel’s back. To be honest, such a level of concentrated dependence is probably not a sensible foundation on which to build our higher education system.

Clearly, overseas students play multiple roles in the system. Let’s take a look at how this plays out in different types of HE.

Because overseas undergraduates pay higher fees, there is a strong incentive for universities to recruit more of them. While UK student fees are £9,535, the University of Hertfordshire charges overseas students £14,965, and Oxford charges overseas students between £35,260 and up to £59,260 for high cost subjects.

In most cases universities have expanded, but where this hasn’t happened the result is displacement of UK students. Oxford and Cambridge are interesting examples.

Every year Oxford puts out a press release hailing “record state school admissions”, and sometimes this gets written up in the press. But what they mean by this is not what you might think: they mean that a record proportion of the domestic undergraduate admissions are from state schools. In fact, last year there were fewer admissions from state schools than in 2002.

How can this be? The answer is that overseas students have displaced UK students. This has meant that a dramatic reduction in British students from independent schools has not fed through into higher numbers from state schools. Essentially overseas students have just replaced British students from independent schools.

It is a similar story at Cambridge, though there has been some growth in state student numbers, and there are now more overseas undergrads than British students from independent schools.

In the absence of significant Oxbridge expansion, the net effect is that any brain gain we might have hoped for from the overseas students has been cancelled out by the brain drain as students from independent schools head for America, many permanently.

It is interesting that two institutions often thought of as similar should have shifted to more overseas students at different times: Cambridge steadily after 1996 and Oxford sharply after 2007. Nor is there any clear connection to UK fee rates. Big increases in real terms fees in 2006 and 2011 don’t seem to have done anything to arrest the trend, while the real terms erosion after 2017 has coincided with the share stabilising – at least in Oxford. I don’t know why this is.

Higher education has changed a lot in recent years. As David Kernohan noted in a recent piece:

“For the first time in the history of HESA data the higher education sector awarded more taught postgraduate qualifications than first degree undergraduate qualifications. And some 64 per cent of these were awarded to non-UK students.”

The great growth area in UK universities over recent years has been taught postgraduate qualifications for overseas students, which have more than doubled. Within this total almost all – 92% – are taught postgraduate qualifications like masters. Only 8% are research qualifications like doctorates.

This growth in taught masters for overseas students is concentrated in a few subjects: overwhelmingly it is in business studies, with a bit of technology, IT, social care and social sciences thrown in.

This change is all the more striking as numbers coming from the EU actually fell back – from about 7% to 2% of new entrants: but rapid growth from developing countries outside the EU offset this.

In 2022/23, 38% of all new higher education students had resided in a non-EU country prior to starting their studies, compared with 23% in 2018/19, so not far off a doubling of their share.

Looking at the period from 2014/15 to 2023/24, the total net growth in numbers at all levels of study was about 590,000. This was split roughly equally between UK and non-UK students, though this represented a faster rate of growth for overseas students as they were fewer in numbers.

About 160,000 of the growth was in Russell Group universities. The patterns were quite different between the Russell Group and the rest.

The share of undergraduates from overseas did increase for the Russell Group Universities, but actually only rose very slightly for other institutions, as there was equivalently rapid growth in students from the UK.

In contrast, while the share of postgrads from overseas increased across all institutions, the increase was much more dramatic outside the Russell Group – the share of students on taught postgrad courses coming from overseas increased from under a third to over half.

And now here is the same data as absolute numbers. Media discussions about migration sometimes imply that many of the people coming to study will be research scientists. But non-UK students doing research postgraduate qualifications (like doctorates) are a trace element within the system – accounting for 13,500 of the 1,053,000 qualifications awarded by UK universities in 2023/24 – 1% of the total.

A large number of institutions now have over a third of their students from overseas.

Many of the institutions that have seen the most dramatic growth are those which have opened a London campus and focussed on taught masters. In some cases there is a sort of “Wimbledonisation”: the institution may be British but most of the students aren’t any more.

I have written before about the costs and benefits of student migration. As the charts in this post hopefully show, student migration is not a homogenous thing.

Some people think it is a costless source of free money for our universities, an unalloyed good. But as the Home Office suggest, this isn’t quite right. Both the costs and benefits are complex.

On the costs side of the ledger we need to think about how likely students are to stay, and what their economic impact is likely to be while they are here, and over the longer term. The 16,000 students who went on to claim asylum last year have a different cost profile to those who end up staying and working in a high paid job, or to those who simply left.

On the benefits side, we need to better understand what the real benefit is. International students are often seen as a cash cow for universities, but the real world is more complicated. Much depends on what the marginal and average costs are to provide them a place (often different) and how much the university is able to charge. And how that compares to the fees and teaching grants for UK students. Even where a profit is made on an overseas student, it is not obvious that this is a benefit to the wider economy if it is then used to cross subsidise something that is not an economic benefit (and not all HE is).

Finally, although there is expansion, there is also likely some degree of displacement in some universities, meaning that some UK students will leave the UK or not do courses they would like to.

The data we would need to measure all these considerations is lacking in many cases, as the MAC pointed out in a review last year. Most fundamentally, we don’t have a good grip on how many former students have in fact left the country. The MAC found that 41% of post-study work visa holders with earnings “earned less than £15,000” a year, which is not really graduate work. But this is only one of numerous routes that former students take – we would need to look across family, asylum, and other work routes – and get better data on how many are not leaving.

The MAC are supposed to be producing further work on the economic impact of the student route. Their work last year emphasised the humungous data gaps in our knowledge about overseas students.

The one thing we can say with some confidence is that when it comes to measures to control student migration, is that it is not one homogenous thing, and one size is unlikely to fit all.

Source